Psychology

Episode 3: Is Your Phone Making You More Kiasu? with Dr. Jean Liu

According to a study by IMH, about 1 in 3 Singaporeans aged 15 - 65 are reported to have problematic amounts of smartphone usage in their daily lives. But what happens when we’re seeing our peers on their 5th couples trip to Japan on Instagram? Does it make us more “kiasu” about our own lives? Can our brains get so overloaded with digital content to the point of “brain rot?” What can we do to develop healthier relationships with our devices? Behavioural scientist Dr. Jean Liu shares her insights.

Listen to the Full Episode

Available on: Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and Amazon Music.

Subscribe to Void Deck wherever you get your podcasts to get notified when the next episode drops.

Episode Highlights

-

How the “fear of missing out” (FOMO) drives problematic social media use—people who fear missing out are most vulnerable to excessive platform engagement and its negative effects, especially on social networking sites

-

Why the pop science concept of social media providing "dopamine hits" might be oversimplified and what neuroscience actually tells us about our brains on screens

-

The truth about "brain rot" and why consuming "mindless" content isn't necessarily harmful

-

How our phones are changing the way we remember and behave, from search-engine-oriented memory patterns to the psychological impact of "phubbing" (phone snubbing)

-

Practical strategies for digital wellness including the concept of "digital minimalism" that focuses on aligning device use with life goals rather than arbitrary screen time limits

Timestamps

00:00 Intro

00:52 What is Kiasu?

01:39 FOMO and Social Media

03:06 Why is Social Media So Addictive?

04:51 Debunking the Dopamine Hit

06:42 Brain Rot

09:10 Effects of Screentime on the Brain

11:03 Healthier Relationships with Devices

13:25 Being Present for Others

14:37 Final Thoughts: Is Your Phone Making You More Kiasu?

15:12 Outro

Guest Biography

Dr Jean Liu is a Director at the Centre for Evidence and Implementation, and adjunct Assistant Professor at Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School and the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine.

Her primary research area focuses on how digital devices impact our health and social relationships. To date, she has published >30 research papers on topics such as: how individuals use their phones during meals, how social media relates to mental health, how WhatsApp users transmit health messages, and whether following Taylor Swift predicts better mental health outcomes.

In recognition of her expertise, Dr Liu has served as consultant to the World Health Organisation, assisting with the roll-out of a new mental health framework for the Western Pacific Region. She is also a Council Member for the Agency for Care Effectiveness, expert panelist for the Health Promotion Board, and board member for several non-profit organisations. Her research insights have been discussed in parliament, and she speaks frequently in the media.

Transcript

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and readability.

JANICE: This is Void Deck, a podcast from Science Centre Singapore exploring local science stories. I'm your host, Janice. Today, we're asking: is your phone making you more kiasu? According to the Institute of Mental Health, 1 in 3 Singaporeans struggle with problematic phone use. Could doom-scrolling and social media addiction make our brains more fearful of missing out? To help us understand the psychology behind our screen habits, we talked with behavioural scientist Dr. Jean Liu.

[Short musical interlude]

JANICE: Dr. Jean, welcome to the show. Before we dive into the questions, would you like to give a quick introduction about yourself to our listeners?

DR. LIU: Yes, I'm a psychology researcher and I specialise in looking at the impact of technology like social media and screen time on youths.

JANICE: Awesome. So firstly, what is kiasu-ness, and is it something that can be measured or studied?

DR. LIU: Yes, kiasu-ness is when you kind of look over your shoulder and you think, ah, that person is doing something and, or, that person has something that I want, and you feel you need to go and get it too, or do the same thing.

It's actually not a Singaporean phenomenon, even though we often say, ah, Singaporeans so kiasu. The West call it FOMO, researchers call it social comparison. It's the basic idea that we turn over our shoulder, look at somebody else, and we want that too.

Of course, the Singaporean story that we tell is that if the hawker centre has a queue, we must join it, even if we don't know what it's selling. That is fear of missing out. The West would call it the fear of missing out.

JANICE: So you would say that the culture of the kiasuness that we have as Singaporeans will make us more susceptible to FOMO, when using social media?

DR. LIU: Yeah, it's funny. I think researchers often link the two together. First, let me unpack social media a little bit. That term actually means quite a lot of things, the landscape has changed quite a fair bit.

It's everything from your social networking sites, and that's what most people think about, your Facebook, your Instagram, to the content sites like YouTube, and then you also have your messaging [apps] like WhatsApp, and of course there are the hybrid ones as well that combine a few of these features.

When we think about FOMO, most of the research has been done on FOMO and the social networking sites. The typical story that we hear, and what research seems to find, is that if you are very afraid of missing out, then you are most vulnerable to using social media the most, especially the social networking sites like Facebook and Instagram, and you're also most vulnerable to the negative effects of it.

So for example, if you are left out in a WhatsApp group, that's going to affect you the most if you're very FOMO. Otherwise, if you’re quite thick-skinned, and you know, you don't really care what's going on around you, it seems you aren't as affected by the consequences of social media.

JANICE: In that case, from a neuroscience perspective, why do you think social media is so addictive? I personally would like to know, because I, too, find a hard time trying to disengage from social media. Why do you think it's so addictive?

DR. LIU: Yeah, I think again, we think of the different range of social media platforms, right, we have the Tik Toks, the YouTubes, where there's the infinite scroll. We just keep watching over and over again. When we stop, something automatically plays, and then, you know, we thought we're going to spend half an hour on it, all of a sudden, we have spent three hours on it.

JANICE: Yes, correct.

DR. LIU: Time flies from us, and I think no one will deny that it's enjoyable, right? I mean, we watch it cause it's fun to watch. In an earlier generation, television was like that as well, right. It's an enjoyable activity, and then time flies.

Of course, there's the other side as well. The WhatsApp messages that keep coming in. There's the Facebook, Instagram notifications that keep coming in, and that, I think, works on a different level.

Psychologists liken it to gambling sometimes. We ask ourselves, you know, what makes something rewarding, and the kind of way that rewards are given is intermittent. You cannot predict [it], and then it comes up every once in a while. That kind of reward contingencies make you use it the most.

So things like WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram, you know, you can't really predict when someone is going to give you a like, reply your messages, so you keep checking.

I think there are some things that are inbuilt, some things that by nature they're rewarding, and therefore we sometimes feel ourselves not being able to control our usage or using it a little bit more than we had anticipated.

JANICE: So would you say that we associate social media as, like, a little platform that gives out gifts to our brain whenever we receive likes?

DR. LIU: People often say, oh, the dopamine hit. You often hear that word, the dopamine hit. I always try to break down the evidence a little bit, as a scientist.

Skeletal formula of dopamine. Source: Wikimedia Commons

What do we mean by the dopamine hit? There's no denying that yeah, it's rewarding, but actually there's very little research that tells us that when you use a digital device, you get a dopamine hit.

To actually say that, yeah, dopamine is released at that point of time, you need to use something called a PET scan [Positron emission tomography scan], and that's when you, you know, inject a radioactive tracer, and that helps you to see as a proxy whether there's dopamine activity in the brain.

Positron emission tomography machine. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

So one study has done that in 1998, involving eight people.

JANICE: Woah.

DR. LIU: What they found was that, yeah, after people play a video game--so not even the modern [devices]--this was 1998, right, so [they found playing] the video game, it's consistent with some level of dopamine release. And that study has been used a lot to say, aha, see, when you play, when you [have] screen time, you get a dopamine release.

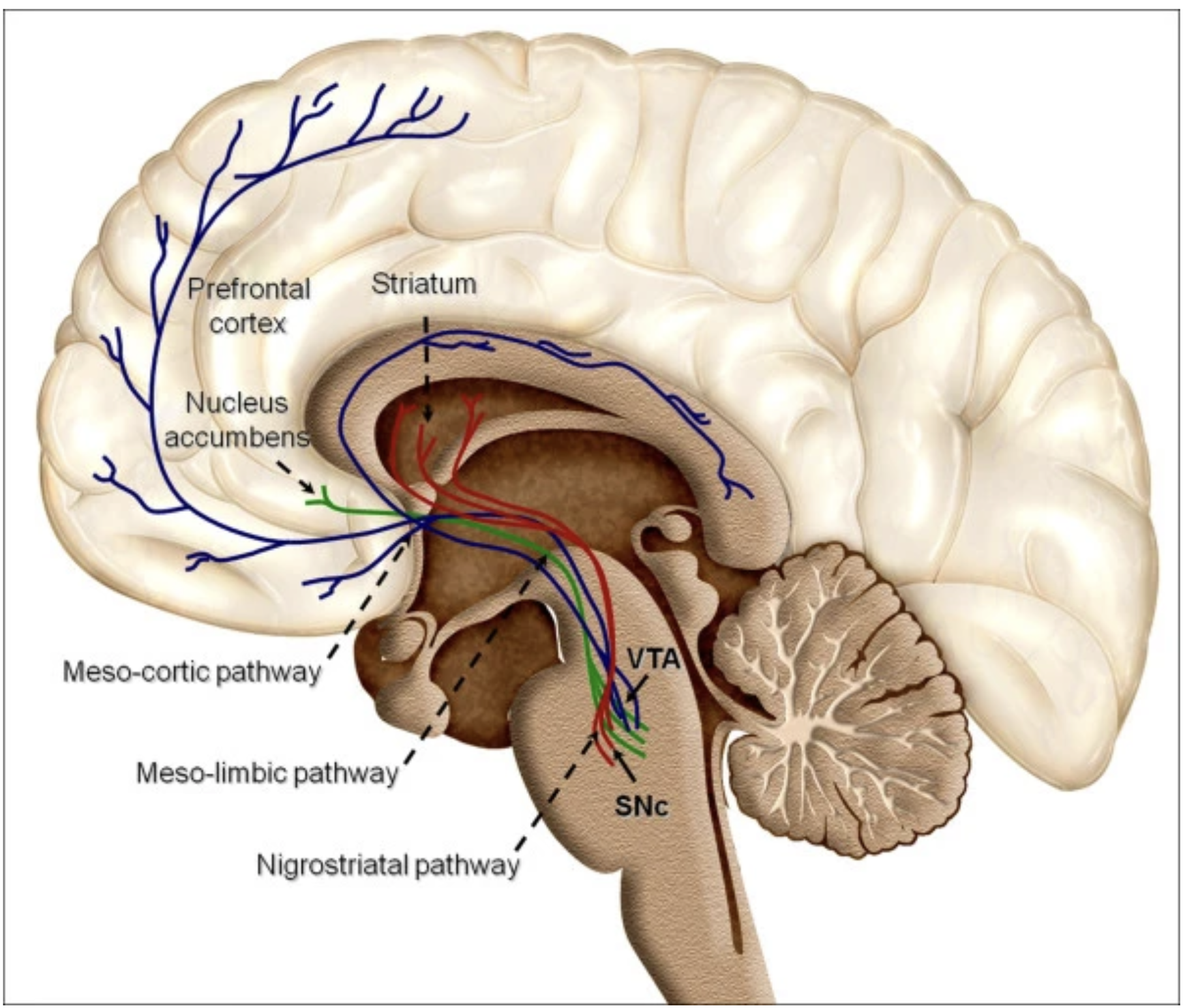

But actually researchers will then take a pause and say, what does it mean to have increased dopamine release? Because dopamine is involved in a lot of other things like movement. Working out probability. So just because you see a dopamine increase doesn't mean it was addictive.

The other side of the neuroscience research tells us that you know, yeah, it's true that when you anticipate getting a social media like, when you anticipate receiving a message from a friend on WhatsApp, or seeing a TikTok video, you have increased activity in the ventral striatum, which is a part of your brain involved in rewards.

But anticipating anything that is nice, [something] people enjoy, like money, photographs of attractive people, food--anticipating any of these also has the same kind of neural activity, so it just means that yeah, we find it rewarding. That's I think as much as you can say about the neuroscience of it.

Overview of reward structures in the human brain. Source: Oscar Arias-Carrión1, Maria Stamelou, Eric Murillo-Rodríguez, Manuel Menéndez-González and Ernst Pöppel. Dopaminergic reward system: a short integrative review, International Archives of Medicine 2010, 3:24 doi:10.1186/1755-7682-3-24.

JANICE: Speaking about that, recently, I believe there's a lot of buzz about this thing called “brain rot.” Not sure if you heard of it. It's a slang term that describes the supposed mental decline from consuming too much trivial or low-quality online content. But in your take, is brain rot actually real? Does exposure to this kind of content actually affect our brain functions?

DR. LIU: I think we, as a society, always feel the need to be productive at all cost[s], and so if we see what we term brainless content, we feel [guilty]. I mean, it was in the case of television as well, right, where people, parents often would tell kids, how are you watching that kind of content, can't you go and study? Can't you do some, watch an educational show instead?

Even for adults, we feel that pressure. Sometimes we should be reading an e-book. We shouldn't, you know [be consuming other content], but actually, if you think about your own life, there are just times when you're tired and there's no way you're going to do an online course at that point of time.

You just want to relax, and I think much of this, what we call the “brain rot,” serves a purpose, which is to help us relax. Just like how in a different generation you turn on the TV at the end of the day, and there's nothing wrong with doing that.

In fact, sometimes researchers now tell people who are insomniacs having difficulty sleeping that maybe some screen time can help you wind down and go to sleep, which is counter-intuitive, I mean, for a long time, people thought that it was the other way around. You watch screens, you won't be able to sleep, but now they're finding out that hey, actually, it helps you to wind down.

So there's nothing wrong with watching some, what people would call, “mindless” content. I think where it becomes a problem is two areas. One, sometimes the content is a lot about news, and if you spend too much time searching about news, what we know is that people get anxious because often news is negative. We hear about the geopolitical crisis. We hear about climate change. You hear so much of it and you keep checking it, you become more anxious.

The other thing we have to watch for is if we spend too much time on it, and then you neglect all the other things you should do. So I think those are the two things to watch out for.

JANICE: Okay, so actually the supposed “brain rot” is okay. It’s okay content for people to consume--

DR. LIU: -- in moderation!

JANICE: In moderation, yes.

Dr. LIU: Balanced!

JANICE: [Laughs] Balanced, yes. I think this will ensure, you know, people not to feel so worried if they're consuming such content in moderation.

Alright, and so let's move on to our next question of the day, given how common it is for people to be on their phones for hours at a stretch, me included, does being online too much cause your brain function[s], such as memory retention or attention span to deteriorate?

DR. LIU: It's a hard question to ask. I mean, it's a very coarse matter. People have tried to do this kind of research where they say, okay, I'll give you a survey. You tell me how many hours of phone use you've been using, how many hours of screen time over the last week, and I will measure your brain function, or I'll give you a memory test.

First, it's notoriously difficult to self-report how much time you spend on your phone because you tend to use it during the day, so those correlational studies are quite--it's hard to interpret.

Second, now that we use the phone all the time or our laptops all the time, is it meaningful to get a concept like that? Because of course, the activity that you're doing is so different, and the average staff today goes on the computer and works all day on the screen.

Do you differentiate that from the, you know, going on the bus and scrolling through TikTok videos? So I think you have to break it down a little bit and also measure it objectively, and ideally not just through a correlational study, but actually trace people over time, or actually do experimental studies. Those kinds of studies are much harder to do, and people haven't quite done that, or you know, it's just much less.

So the answer is that I don't think the verdict is out on just general screen use and brain development, it’s much harder to trace that.

But we do know about certain activities online that change the way you function. For example, people have found that increasingly we're so used to Googling information that when you ask people about a topic, the way they sort the information out seems to be by thinking, okay, how am I going to Google it [editor’s note: read this TIME article for more on this phenomenon]. So I think it changes the way we organise information and so forth.

[Short musical transition]

JANICE: Now moving on to our next question, what do you think we can do as a society that we can do to develop healthier relationships with our devices?

DR. LIU: We need to find balance. That's the keyword: balance.

JANICE: The keyword for today, balance.

DR. LIU: Balance, because it's not about saying, oh, it's so bad, we need to ban everything, and then you go and hide in your room without a device or any screen time. It's also not about saying it's so good, and there are no problems with it. Somehow in between those two realities, we need to find balance, right.

One of the researchers [editor’s note: Cal Newport] came up with this idea of digital minimalism. It's not about saying, how much time am I using with my phone or my devices? It's about saying, think of your bigger life goals--is this getting in the way of your goals or not? And I think that's a very empowering kind of message, right? It's not about the absolute number of hours. It's really about, is this serving you or are you serving it? And working that out takes some art. But yeah, I think that's the balance that we need.

JANICE: I like that: digital minimalism. Okay, I shall do my part to do that as well. Next question. Do you have any creative or unusual hacks for reducing screen time?

DR. LIU: The complaint many people have is on time use usually, right. Ah, you know, I really need to do this assignment, this report, and it's effortful. Often it's effortful, and then you find yourself going on TikTok. You find yourself scrolling videos, checking your friend’s status updates.

What I often do in those situations is to go somewhere without Wi-Fi, sometimes be a bit more radical or put my phone aside so that I have that focused time in order to do the task at hand, even if it's more effortful. Sometimes people use what we call the Pomodoro technique as well, which is where we say, okay, I'm going to do thirty minutes of focused work, and then I'm going to use my phone for anything that I want, for five to ten minutes, and that also helps people to focus.

I think that often is everybody's biggest complaints for each other. Parents like to say, ah, why are you using your phone again and not doing your homework? But even ourselves, right, and our working lives, we often get distracted, especially for tasks we don't feel like doing.

JANICE: That's true, that's true. So being intentional with your phone time.

DR. LIU: I think the other thing that I want to say is that we're often guilty of not being present for the people around us, and the irony is often we are taking our phones to message, so we're trying very hard to connect with other people online, and this has to do with FOMO as well, right? We don't want to miss out the message from our friends, but then we take out our phone, even when we are sitting and having dinner with somebody else, and that affects the person sitting next to you.

My research group did this line of research, and we found that people find that equivalent to ostracism. They find it horrible. They don't like it, and they feel like, oh, you have left them out.

But we don't think of that. We're just mindlessly taking our phones even when we are in front of people. So my caution is on two sides. I would say, if you are in front of somebody else, you really have to think about how your phone use affects them, and I would say put it away if you can, and if you can't, explain why you're using your phone. The other side, of course, is time use, and if you need to be productive, then take radical steps to do that.

JANICE: Yes, I like that. Being, basically, in the present moment.

DR. LIU: Yeah.

JANICE: Then appreciating those who are around you right now.

[Short musical interlude]

JANICE: Just to wrap up this session, maybe one last question to Dr. Jean. So do you think your phone is making you more kiasu?

DR. LIU: I think it depends. So I'm going to give the careful answer to say it depends on how you're using it. If you're looking at other people's lives and feeling like, oh, why is that person doing that amazing thing, I feel like I'm missing out on something? Then yes, it's making you more kiasu, but if you're using it for healthier ways of connecting with friends, organising activities, then no, it's not making you more kiasu.

JANICE: Alright, thank you so much for joining us, Dr. Jean, and we hope to see you again next time.

DR. LIU: Thank you.

[Outro music]

JANICE: Thank you for listening to Void Deck. Want more Singapore science stories? Head to voiddeck.science.edu.sg, and if you enjoyed this episode, please rate and subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. See you next time and stay curious.

Resources

Dr. Jean Liu’s LinkedIn Profile

https://www.linkedin.com/in/jeancjliu/

Watch Dr. Jean Liu host Byte the Habit, a 6-episode CNA show on

screentime in families

https://www.channelnewsasia.com/watch/byte-habit/journey-begins-5215751

Digital for Life Movement: Positive Use Guide on Technology and Social

Media

http://go.gov.sg/positive-use-guide

FOMO and Social Media | Psychology Today

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-asymmetric-brain/202106/fomo-and-social-media?msockid=1a0bfdea72326f2a2594e83f73686e47

Giulia Fioravanti, Silvia Casale, Sara Bocci Benucci, Alfonso Prostamo,

Andrea Falone, Valdo Ricca, Francesco Rotella. (2021). Fear of missing

out and social networking sites use and abuse: A meta-analysis. Computers

in Human Behavior, 122, 106839.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106839

Koepp MJ, Gunn RN, Lawrence AD, Cunningham VJ, Dagher A, Jones T, Brooks

DJ, Bench CJ, Grasby PM. Evidence for striatal dopamine release during

a video game. Nature. 1998 May 21;393(6682):266-8. doi: 10.1038/30498.

PMID: 9607763.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9607763/

FOMO Is Real: How the Fear of Missing Out Affects Your Health | Cleveland

Clinic

https://health.clevelandclinic.org/understanding-fomo

Subramaniam, M., Koh, Y. S., Sambasivam, R., Samari, E., Abdin, E., Jeyagurunathan, A., Tan, B. C. W., Zhang, Y., Ma, S., Chow, W. L., & Chong, S. A. (2024). Problematic Smartphone Use and Mental Health Outcomes among Singapore Residents: The Health and Lifestyle Survey. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 98, 104124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2024.104124

About one in two S’porean youth has problematic smartphone use: IMH study

https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/about-one-in-two-s-porean-youth-has-problematic-smartphone-use-imh-study

Commentary: A digital detox won’t reset your busy life - CNA

https://www.channelnewsasia.com/commentary/national-day-unplugging-impossible-handphones-digital-minimalism-2535626

MOH Guidance on Screen Use in Children (First Published March 2023, Updated

January 2025)

https://www.moh.gov.sg/others/resources-and-statistics/guidance-on-screen-use

How Google Changed the Whole Way We Think About Information | TIME

https://time.com/5383389/google-history-search-information/

On Digital Minimalism - Cal Newport

https://calnewport.com/on-digital-minimalism/

Scientists Say: Ventral striatum | Science News Explores

https://www.snexplores.org/article/scientists-say-ventral-striatum

Want to learn more about psychology? Embark on a journey of self-discovery

and find out the psychology and physiology of fear at Science Centre Singapore’s

exhibition Phobia²: The Science of Fear:

https://www.science.edu.sg/whats-on/exhibitions/phobia-the-science-of-fear

To explore how we perceive and think about the world, watch Dr. Jean Liu’s Science Centre Singapore UNTAME Star Lecture 2024: More than Meets the Mind at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3jiSf23Cb3Y

Credits

Special thanks to Dr. Jean Liu for coming on the show. This episode of Void Deck was hosted by Janice Tow. The episode and series was produced by Jamie Uy. Audio engineering and pre-production research were provided by Ewan Leong. Video teasers were edited by Lydia Konig. Studio production was assisted by Jane Stephanie Emmanuella and Ai Xin Qin. Season 2 music and graphics were created by Ai Xin Qin. The cover art was illustrated by Vikki Li Qi. The Void Deck podcast is an original transmedia production by Science Centre Singapore.

Last updated 4 December 2025