Prof Brian Cox Shows Us The Solar System

We chat with rockstar physicist Professor Brian Cox on his latest BBC astronomy series, Solar System. Read his musings on voids, the mind-boggling scale of the cosmos, and the (theoretical) acoustics of an outer space concert.

Diamonds raining from the heavens through 1000kmph winds. An erupting volcano the size of Mt. Everest. Dust devils ripping serpentine shadows across red sand dunes. A subterranean ocean with more water than all the Earth's oceans locked beneath a 150-km-thick ice crust.

You've never heard of a weather report quite like this. However, these unfathomable, astonishing events are just another Tuesday on the other worlds in our cosmic neighbourhood.

BBC Earth's newest astronomy series, Solar System, launches audiences from their living rooms into outer space to tour these alien vistas with cutting-edge VFX techniques.

Presented by rockstar physicist Professor Brian Cox, Prof Cox walks viewers through the science behind these mysteries. Journeying to breathtaking natural wonders on Earth, Prof Cox explains the physics and geology underpinning new findings from over 40 active spacecraft roaming the vast backyard beyond our planet.

The Void Deck team had the pleasure of interviewing Prof Brian

Cox in advance of the series premiere. We discussed his favourite space

photograph, what voids—cosmic nothing—can reveal about everything, and

how he grapples with the mind boggling scale of the universe. We also ask

the former keyboard player about the acoustics of holding a (hypothetical)

concert on another world.

Stream episodes of Solar System on BBC Earth, available on BBC Player.

The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

VD: How does Solar System compare to other BBC astronomy series you've done in the past, like The Planets and Universe?

PROF BRIAN COX: The basic idea was a snapshot of our solar system as we see it and observe it today. We have over 40 spacecraft active currently in the solar system. These spacecraft are sending back more data than ever before. Could we make a series that was absolutely up to date, based on the data as it comes in?

The first episode, the initial idea was volcanic worlds. We have a lot of recent observations of volcanic activity, including very interestingly, very recently, volcanoes active on Venus, which was a reanalysis of all the data actually. But then the question becomes, well, is it just about volcanoes?

It became a film about thermodynamics in a way. The laws of thermodynamics are interesting because if you think about what life is, it's a process. Energy has to move between hot things and cold things, for example, in order to produce complex chemistry. So then you end up with a film that's about thermodynamics and the relationship of thermodynamics to life.

Prof Brian Cox and crew at Eldhraun Lava Field. Photo credits: BBC Studios

VD: What do you think is the biggest change in our understanding of the universe from the previous series to now Solar System?

PROF. BRIAN COX: When I made my first series, Wonders of the Solar System, we hadn't been to Pluto. It was just a fuzzy dot in the sky. When New Horizons launched, by the way, it was still a planet. [Pluto] was reclassified to not be a planet when the spacecraft was in flight. It kind of got relegated.

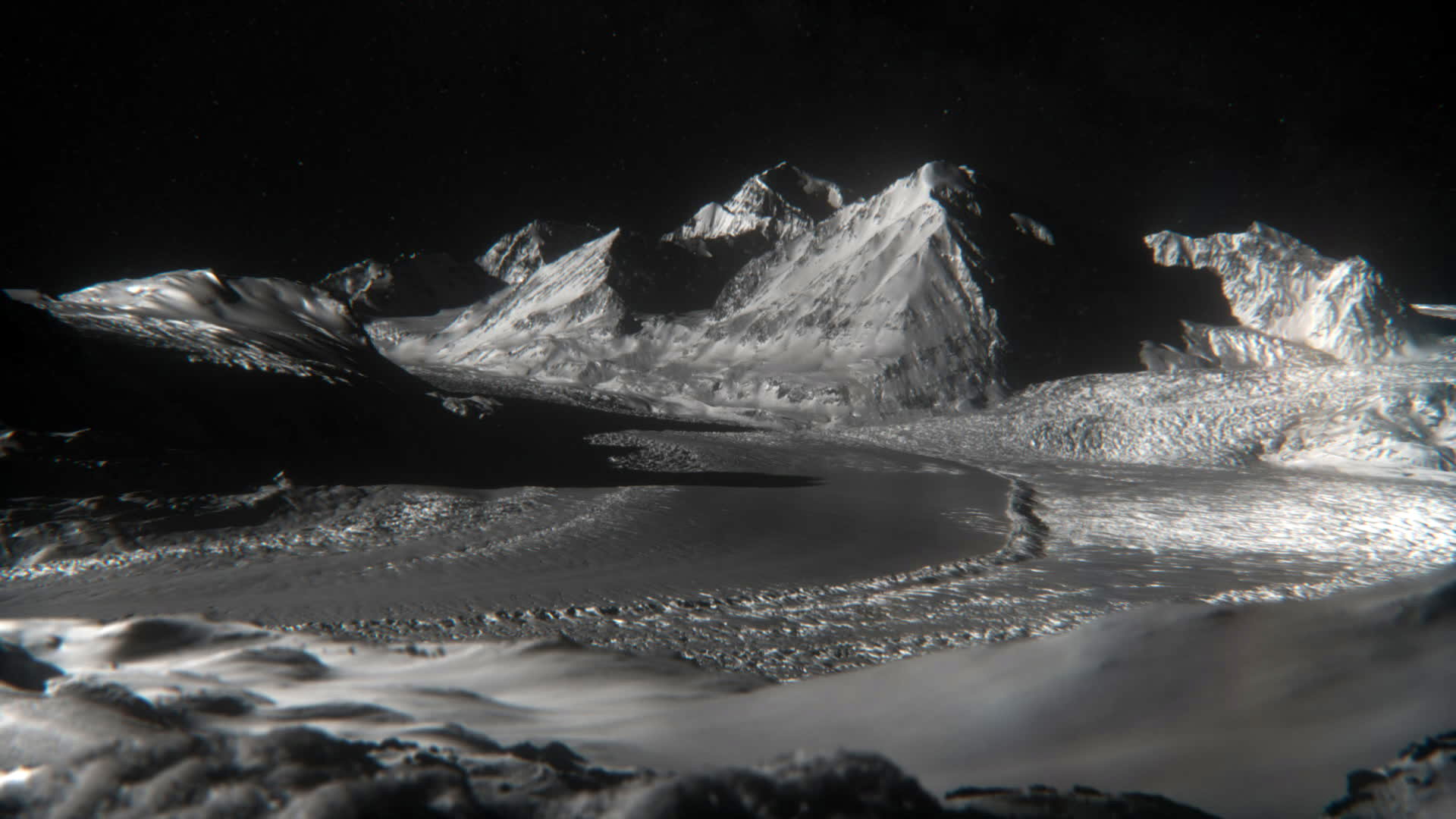

But when we got there, it turns out this world is geologically active. It has glaciers on the surface that flow down the valleys and canyons. They look similar to the glaciers on Earth. Indeed, we filmed and talked about that in Alaska, one of the great glaciers at the foot of the Denali Mountain. But it can't be because it's well below minus 200 degrees Celsius on the surface. So they can't be the same. They can't be made of water.

They're not. They're made of nitrogen ice. Then you get into a discussion about chemistry and why nitrogen ice at these very low temperatures may behave like water ice does on Earth.

A still from Solar System Episode 4: Ice Worlds showing Pluto’s glaciers through VFX. Image credits: BBC Studios

I think Pluto was a surprising world. In the series, we spend a lot of time talking about things that aren't planets or even moons. We're discovering and learning a lot more about objects out there beyond the orbit of Pluto in what's called the Kuiper Belt, for example, which we really hadn't seen before in any detail.

Indeed, the New Horizons spacecraft visited one of those objects. These small objects, these strange worlds, are becoming increasingly interesting because in many ways they help us understand the history of the formation of the solar system.

VD: To understand these laws of thermodynamics underlying these spectacular events happening on other planets, you travelled to some extreme locations here on Earth, from caves to deserts, and as you mentioned, Alaska. Could you share a memorable experience you had on location?

PROF BRIAN COX: Well, Alaska was very interesting and beautiful. It's spectacular. But we filmed there in February, in the winter.

They said to me, it's okay, because it's going to be zero degrees. Okay, right. But they meant 0 degrees Fahrenheit, because it's America, which is minus 20 or minus 30, whatever it was [in] Celsius. So it was challenging to film in Alaska.

Also the only way you can get to Denali is to fly. We flew in on a plane with skis attached to it and landed on the glacier, which is an incredible experience for someone that likes planes, to be able to land on a glacier in an aircraft. So just getting to some of the places was exciting.

Prof Brian Cox and crew at Denali National Park, Alaska. Photo credits: BBC Studios

VD: Speaking of these extreme feats of aircraft and spacecraft, there's these wonderful bits in the series when you show photographs, almost like postcards from distant planets. Was there a particular image transmitted by one of the spacecraft that really stayed with you?

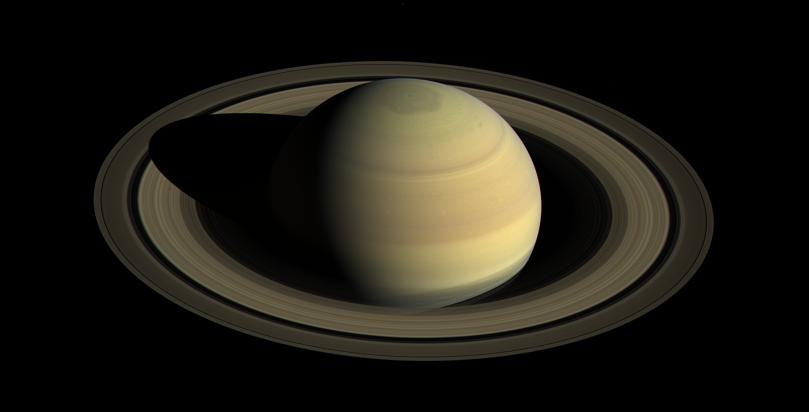

PROF BRIAN COX: The photographs from Cassini, which is an older spacecraft actually, of Saturn, Saturn's rings, and in particular a moon that we focus on in the series called Enceladus, are remarkable images.

You see the complexity out there. The rings are water ice, basically, very thin, maybe only a few metres thick, that go around this planet. Obviously the most distinctive feature of Saturn. You get into questions about how that beauty and complexity emerges from these very simple laws, the law of gravity in this case, basically Newton's law of gravitation. Everybody can write it down, but it's capable of producing this majesty around the planet.

Those images are, for me, the most spectacular images currently that we have of the solar system.

Saturn seen from Cassini in April 2016. Image credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

The other one is at the other end of the scale. There's a moon of Neptune called Triton I've always been fascinated by. We only have one spacecraft, Voyager 2, that was launched in the 1970s and flew past in the mid 1980s and flew through the system.

We only have a few images of this world. It orbits the wrong way around Neptune. It's made of the same stuff and formed in the same region as Pluto, but it got captured by Neptune's gravity and so it behaves very differently. We built this picture of this really odd, beautiful, active world on the frozen edge of the solar system from just a few images.

One of my favourite images of all is from Voyager 2. It's a photograph it took as it left the Neptune-Triton system, going out forever into interstellar space and took this picture of the two crescents of Neptune and Triton together. That has always been my favourite photograph of the solar system.

Voyager 2’s departing view of Neptune and Triton. Photo credits: NASA / JPL-Caltech / ISS / Justin Cowart

VD: Science Centre Singapore's new e-magazine is titled Void Deck. The name is a play on what Singaporeans call the open areas in the ground floor of public housing, and the idea of cosmic voids. How would you explain voids and what they might tell us?

PROF BRIAN COX: The universe is basically one big void. These planets and moons, which are essentially everything to us, are really specks. Most of the universe is empty space.

Although, empty space isn't empty. If you start to go deeper into theoretical physics and nature, then you find that there's no such thing as a void, as emptiness. The vacuum, as we call it, is filled with activity. Actually, one of the most famous calculations that showed us that that matters is Stephen Hawking's calculation of the temperature of black holes.

Black holes are just space and time. They're just a distortion in space and time, according to Einstein. Just geometry. Yet Stephen Hawking found that it has a temperature. Indeed, we now strongly believe that they store information. But it's coming from calculations which are really based on an understanding of what's called the quantum vacuum.

The interesting answer to your question, I suppose, is that there is no such thing as a perfect void.

VD: That's lovely. From something that looks like nothing, we can actually understand almost everything and gain a better understanding of the universe.

PROF BRIAN COX: Yeah, the understanding of nothing. The study of the vacuum [is] almost all there is in theoretical physics. [Laughs] Understanding the quantum vacuum is basically it, really–to an extent. When you print that, put in brackets that I was smiling when I said it. [Smiles] There are many physicists who would say, but what about…?

VD: When you're studying something as vast as the universe—which can make one feel very small—how do you stay grounded?

PROF BRIAN COX: I did some live shows with an orchestra recently [at the] Sydney Opera House. I hope to bring it to Singapore at some point. The idea of that show was one question, well, two questions basically. I start the show by saying that when you think about cosmology and astronomy, the question that arises is: what does it mean to live a finite, fragile life in an infinite eternal universe? You can't avoid that question when you think about the cosmology and what we've discovered about the size and scale of the universe.

The music we used [was] a lot of Richard Strauss, Richard Strauss' “Zarathustra”, which everybody knows from the opening of 2001. But there's another 28 minutes of it, which is [a] beautiful exploration of the question. Strauss, at the premiere of that piece, said that this piece is about one question: how can we justify our existence when faced with the unlimited power of nature?

That is the question that occurs to you when you think about even a little thing. In astronomical terms, the sun is little. It's a small star that can fit about a million Earths inside, but it's pretty average. What does it all mean? How am I to understand these discoveries in a human sense?

People have written great music, great literature about this. They've created great art, all exploring this question. Science then becomes one of the lights you can shine on these deeper human questions. A necessary light, but not sufficient on its own.

VD: Before you became a physicist, you were a musician. I have to ask–this may be a bit frivolous. Theoretically, if humans could survive the journey and you could attend a concert on either Venus or Titan, what might it sound like?

PROF BRIAN COX: [Laughs] Well, on Venus, the atmosphere is 90 times atmospheric pressure here on Earth. The temperature is well in excess of 400 degrees Celsius. I don't know what you'd make the instruments out of.

But the acoustics of Venus, that's an interesting question. I mean, you can go to a helium atmosphere, and then we know what our voice sounds like. It affects our vocal cords because of helium and the differences in partial pressures and all those things. Your voice sounds really high. If you can even speak about how your voice would sound in excess of 400 degrees Celsius, at 90 atmospheres pressure–obviously you can't, right? Because you'd just be completely squashed and vaporised.

It's an interesting simulation to do. You’re right. What would sound waves sound like, if you could put a loudspeaker there and send sound waves through the atmosphere? I should probably know the answer to that, but I've never thought about it before. So I [should] sit here for a couple of minutes, which is what you should do as a scientist and look at the equations that govern how sound waves move through a medium.

That kind of question becomes very important when we're looking at the cosmic microwave background radiation and the way that sound moves through the universe in the early universe when it was a plasma. So before 380,000 years after the Big Bang, when the first atoms formed. These questions are actually very important questions, simulating how sound waves move in different mediums, in different temperatures, and pressures.

Titan is probably nicer. It's very cold. It's got lakes of liquid methane on the surface. I think it would probably be more likely that we could have a concert on Titan, although we'd have to be very warm. If I was to choose, I would go to the Titan concert rather than the Venus concert. You'd at least have a chance on Titan.

Written by Jamie Uy

Featured image courtesy of BBC Studios

Last updated: 1 November 2024