Kopi, Caffeine, and Me

An Australian PhD researcher’s quest for caffeine in Singapore and how a love for espresso became an unexpected journey through the chemistry and culture of kopi.

A collage showing scientists brewing a traditional cup of kopi. Illustration credits: Ai Xin Qin.

I’ve recently arrived in Singapore for a PhD research internship at Science Centre Singapore. Coming from Perth in Western Australia, espresso is my go-to, whether brewed at home or grabbed from a local café. But in Singapore, espresso is more expensive. Buying it here would quickly burn a hole in my wallet. That’s when I decided I couldn’t leave my coffee fate to chance.

Before flying out (after one too many luggage-scale battles and tense, Tetris-style negotiations with my carry-on), I had to face facts. The espresso machine wasn’t coming with me. It is not exactly designed for international travel.

I wasn’t about to let this disrupt my routine. Without coffee, I’m like a Wi-Fi signal with one bar, technically working, but painfully slow and likely to drop out at any moment. Coffee is more than just a ritual; it’s my lifeblood. It’s the first thing I reach for in the morning, the only thing keeping me awake after lunch, and the fuel that powers my entire day.

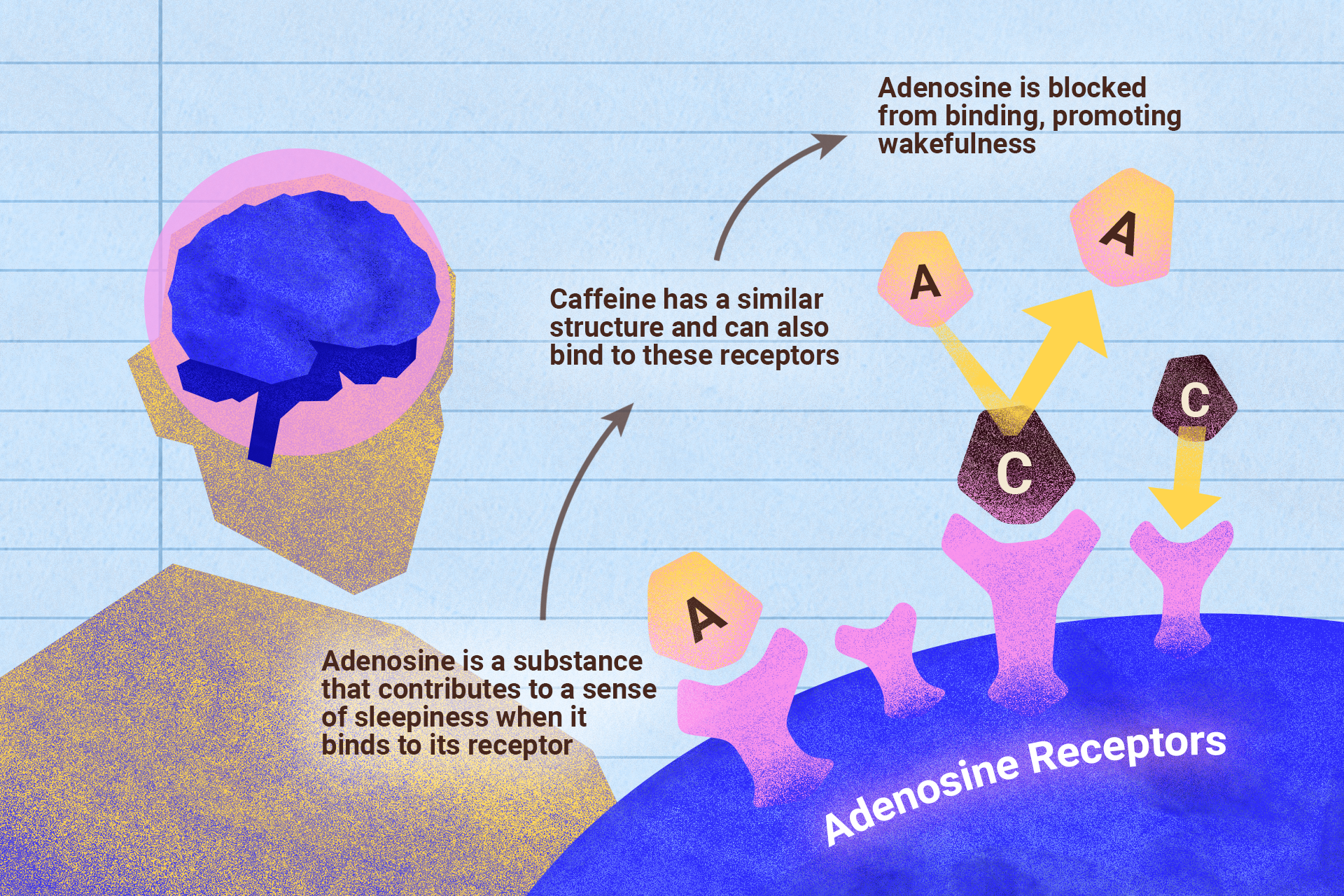

How caffeine works. Illustration credits: Ai Xin Qin.

So, I chose to pack a portable option, a handheld electric espresso maker. When I stumbled across this online, I couldn’t believe what I saw. A portable espresso machine? I had no idea such a device even existed, but as soon as it popped up in my search results, I knew I had to try it. Picture a short black in a frosted demitasse cup, crowned with a thick crema, reminiscent of the froth on a cappuccino. The device claimed to deliver espresso-style coffee using ground beans, with the option for quick and easy brews using coffee pods.

It arrived with bold promises of ‘Espresso anywhere!’ and looked every bit the part. Picture a short black in a frosted demitasse cup crowned with a thick crema, reminiscent of the froth you’d find on a cappuccino. The device boasted espresso-style coffee using ground beans, with the option for quick and easy brews using coffee pods.

A portable espresso maker in action. Video credits: Simon Daniele.

I unpacked it on my first morning in Singapore. This piece of high-end tech looked as impressive as the marketing promised. Of course, once I started using it, the cracks in the marketing claims began to show. “Precisely like an espresso machine,” it claimed. Well, let’s just say it tried. The result was drinkable, but it was no espresso. Purists might call it a very enthusiastic long shot, but espresso coffee it was not, by a long shot.

I also unpacked a handheld manual grinder and one kilogram of freshly medium-roasted Arabica beans. After all, you can’t make great coffee without freshly roasted beans and the right tool to grind them precisely. Using the grinder made me think more critically about something I once took for granted: grind size.

Each type of coffee machine requires a different grind for optimal extraction, and getting that right is key. The freshness of the beans also plays a vital role. While the flavour and aroma compounds in coffee degrade within weeks after roasting, freshly roasted beans release their flavours more readily, making a significant difference to the final brew. Caffeine content, however, remains relatively stable over this period.

Interestingly, as I discovered years ago, the freshness of the beans can even affect how the machine performs. Brewing coffee is a science experiment where variables like time, temperature, pressure, grind, and bean freshness all contribute to the final result.

A comparison of grind size and brewing time for cold brew, French press, pour-over, and espresso. Illustration credits: Ai Xin Qin.

A fine grind suits espresso’s quick, pressurised burst. A coarse grind works better for longer brewing styles like cold brew. Use the wrong grind, and you’ll either under-extract (sour and weak) or over-extract (bitter and unpleasant). The difference? Flavour, scent, mood, and most importantly for me, caffeine. Because let’s be honest, it’s the caffeine I’m chasing.

Which brings me to my favourite Singaporean discovery, kopi.

It’s more than just coffee. It’s culture in a cup. Often served at coffee stalls in hawker centres and traditional cafés, it’s brewed with robusta beans, sock-filtered, and flung between kettles for cooling and aeration. The menu? It was intimidating at first. Kopi-O, kopi-C, sweetened or less sweet, evaporated or condensed milk, hot or cold, in a bag or a cup, for here or takeaway.

A guide to Singapore kopi. Illustration credits: Ai Xin Qin.

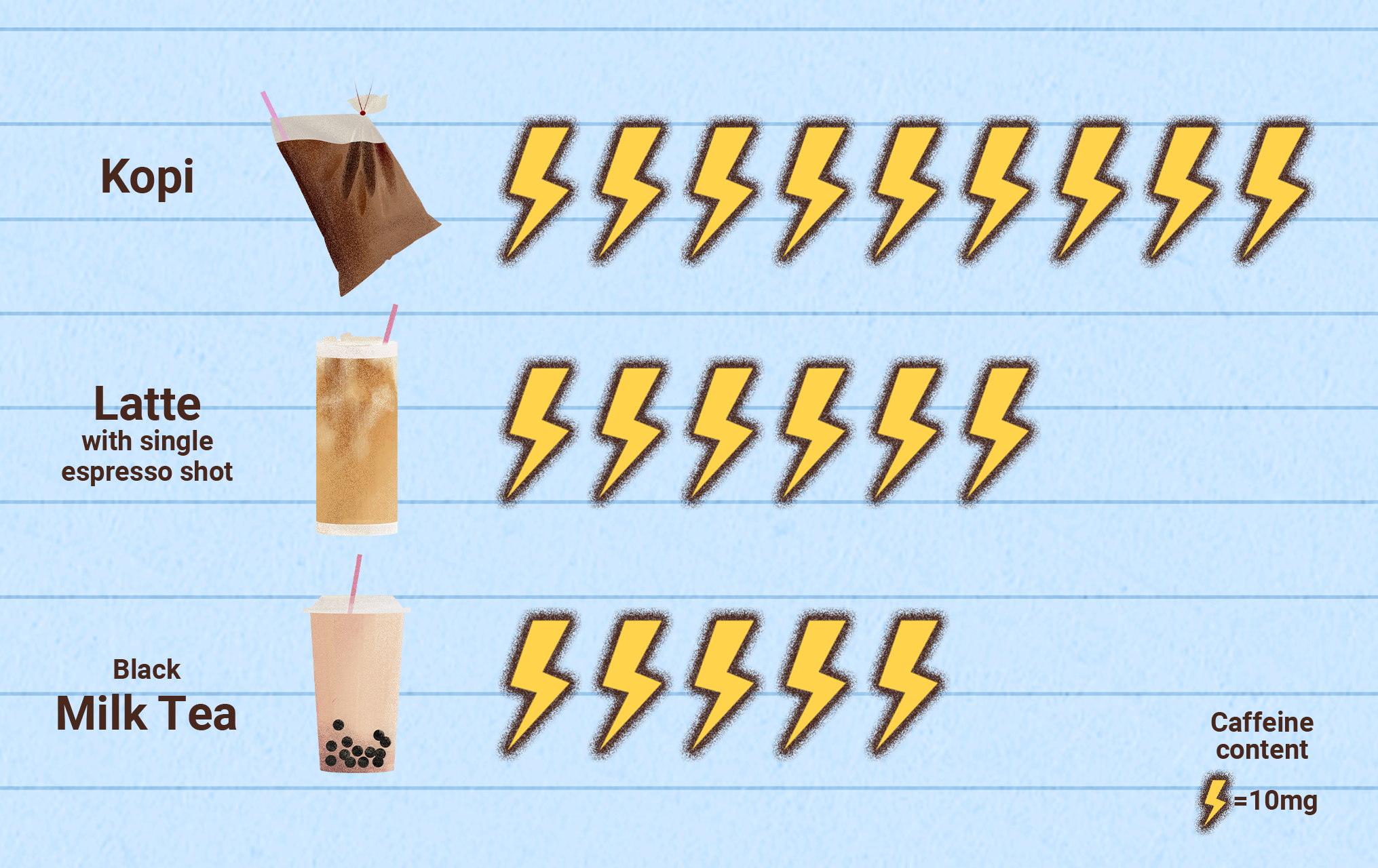

Initially, I assumed kopi would have less caffeine than a traditional

espresso. After all, kopi is less concentrated than espresso. But after

a few mornings spent buzzing through to-do lists at twice my usual speed,

I started to wonder.

It turns out that caffeine intake isn’t just about the taste of the coffee.

It is also influenced by how it’s brewed and the dose. Kopi often uses

more grounds, a longer steep, and a larger volume per serving, which can

result in a higher caffeine dose than a single espresso shot.

The surprising caffeine kick of kopi reminded me of the summer I started

drinking cold brew. The extraction process for cold brew is a lot slower.

It is made by steeping coarsely ground coffee in cold water for 12 to 24

hours. This long extraction time allows the coffee to release more caffeine,

without the bitterness typically associated with hot-brewing methods. So

even though it doesn’t taste as intense, a standard cold brew serving often

has a higher caffeine content than hot-brewed coffee overall. Cold brew

is smooth and mellow in flavour, but I was drinking so much of it that

I developed a suspicious eye twitch.

A strong coffee flavour does not necessarily mean you are getting more caffeine, as milder-tasting types may lead you to drink more, potentially increasing the overall effect.

Caffeine content per standard serving of kopi, latte (with single espresso shot), and black milk tea. Illustration credits: Ai Xin Qin.

Then there’s the matter of sugar, additives, and general well-being. Arriving in Singapore, I was immediately struck by the A to D health scoring known as the Nutri-Grade labelling system on certain drinks. Singapore’s health campaigns have only heightened my awareness, so I’ve settled into a kopi-C kosong routine with evaporated milk, no sugar, and high satisfaction.

Sure, the black version is healthier, but it’s also about finding that balance between being health-conscious and satisfying my taste buds. From adapting to new brewing tools, experimenting with grind size, and navigating the Singaporean kopi culture, this adventure has taught me that coffee is never just coffee. It is chemistry, culture, and a constant negotiation between flavour, function, and the occasional twitchy eyelid.

Written by Simon Daniele

Simon is a PhD candidate at Curtin University and a member of the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for the Digital Child. As the recipient of a Scitech industry scholarship, he investigates how transmedia learning in Science Discovery Centres fosters problem-solving in children aged 6 to 8. As part of his research, he spent three months at Science Centre Singapore, sharing insights and adapting his framework for institutions in Southeast Asia.

Published 28 May 2025