The Chemistry of Mala Xiang Guo

Love mala xiang guo? Savour this tongue-in-cheek breakdown of the chemistry behind one of Singapore's favourite spicy dishes.

Mala has taken the world by storm—a strong, spicy, scarlet storm that has stirred up countless chilli-craving consumers in its path. In return, it threw out products such as mala xiang guo, mala hotpot, mala fish skin, mala potato chips, leaving mala fans craving for more.

But in the eye of the storm, amidst all the hot hoo-ha, lies two chemical compounds in mala that calmly work their magic to unleash “mayhem” on taste buds all over the world.

Science of Spiciness (The “La” in Mala)

I’m sure capsaicin isn’t new to most of you. It is the chemical compound found in chilli peppers that gives you the "la" in mala. It is responsible for the spiciness we claim to taste.

But hold up! What does “claim to taste” really mean? It turns out that chemical reactions take place between food substances and taste receptors on our taste buds. These chemical reactions are what triggers tastes. There are five basic types of tastes (sweet, salty, sour, bitter, umami), and spiciness does not make it into the list.

So how do we know that our food is spicy? When we consume spicy food, we activate our pain receptors – the very same receptors activated by extreme heat. Imagine slurping piping hot soup or biting into satay right off the barbeque. In both cases, we end up burning ourselves and scalding our tongues. Eating mala has the same effect: warning signals are instantly sent to your brain, tricking it into thinking that you are in actual pain and danger. This, in turn, triggers a series of pretty unpleasant physical reactions: your heart beats faster, your nose starts to run, and you break into a sweat. Buckets of sweat, to be exact.

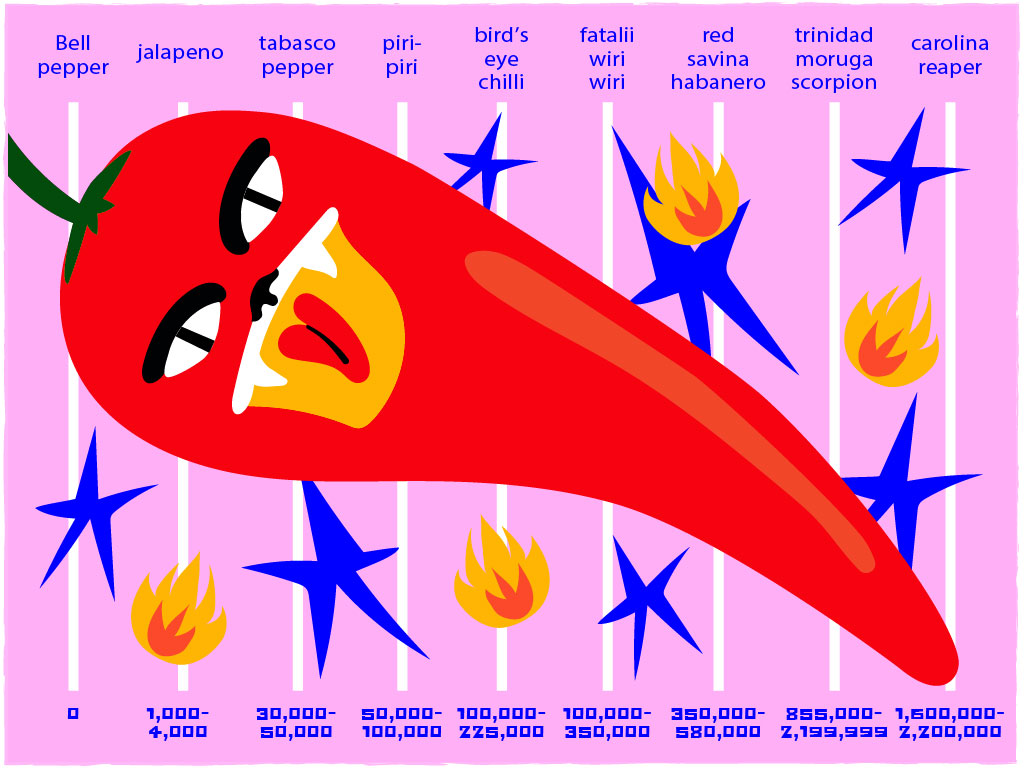

The standard measure of spiciness, however, is not the number of buckets you fill with your sweat (ew!). Instead, spiciness is measured using the Scoville Heat Unit (SHU) and Scoville scale – a scale indicating the varying concentrations of capsaicinoids (a type of capsaicin).

Many can attest that the sweet bell pepper, ranked at 0 SHU, is not spicy at all. Tabasco sauce, a widely popular condiment, enhances dishes with a dash of 2500 – 5000 SHUs of spiciness. At the other end of the scale, we have two contenders in a race to create the world’s hottest chilli pepper. Trinidad Moruga Scorpion and the Carolina Reaper, are both neck-to-neck at 1.5 – 2 million SHUs. What’s more jaw-dropping (and eye-watering) is the U.S Grade Pepper Spray burning at twice the spiciness, a whopping 2.5 – 5 million SHUs.

Let’s get back to the burning question, where exactly would mala fit?

A typical mala recipe calls for dried chilli but does not specify the type

of dried chilli. So to answer this question, we interviewed mala stalls

all over the world Jurong and came to a conclusion. Most mala chefs

use dried “facing heaven” chilli or “heaven” chilli, a cone-shaped medium-hot

chilli pepper of 30,000-50,000 SHUs in their dishes. That fits rather warm

and snugly in the middle of the Scoville Scale.

Science of Numbness (The “Ma” in Mala)

But spiciness isn’t the only factor that makes or breaks a mala dish. Self-proclaimed mala connoisseurs can confidently claim that spicing up the dish with chilli alone is not going to make the cut. Often, mala chefs would throw in a spoonful of this “magical” ingredient into your mala Xiang Guo, an ingredient that causes your lips to burn with a tingling sensation.

Here’s introducing hydroxy-α-sanshool – the chemical found in peppercorns that puts the "ma" in mala. It is responsible for the unpleasant and uneasy numbing sensation that swathes your lips and tongue when you accidentally bite on a peppercorn. Hydroxy-α-sanshool interacts with touch receptors and triggers a tactile stimulus to the brain. The brain then reads this signal and interprets it as numbness, making you think and feel like your lips are vibrating very quickly.

Ma La is Subjective

The combination of capsaicin and hydroxy-α-sanshool, however, has constructed some rather dubious social identities that have led to the breakdown of many relationships. I think you know what I’m talking about…

As amusing as it seems, the reason why some people find comfort in "da la" (big spicy) while others quiver at the sight of "xiao la" (small spicy) is the variation in amount and sensitivity of the aforementioned receptors. Someone who has more pain and touch receptors might, therefore, be more sensitive to and less tolerant of spiciness and numbness; as compared to someone who has less.

And if you suspect that you are born the former, fret not. Studies have shown that continuous exposure to capsaicin increases the amount needed to trigger a similar burning effect. This isn’t because the pain eases up; it is simply an indication that you got tougher, building up an increased pain tolerance. Psychological research shows that some spice-lovers might even feel the same burn as spice-haters, just that they find pleasure amidst the pain.

Whether it gives you pain or pleasure, mala continues to enchant the masses with its signature spiciness and numbness, the teamwork of the chemical duo capsaicin and hydroxy-α-sanshool. Looking at how mala dishes have managed to stay in trend and how mala stalls are still sprouting all over Singapore, it’s safe to say that the mala storm rages on.

Food CSI

If this article has spiced up your curiosity and you're hungry for more food science, don't let your appetite for knowledge simmer down! Take a byte and stream Science Centre Singapore's Food CSI video series in collaboration with Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre. Watch the three-part series to discover what makes Hainanese chicken rice meat so tender, if we can recreate wok hei using bunsen burners, and whether using an arbor press leads to better Nanyang coffee!

Original text by Genevieve Teo

Edited for republication by Jamie Uy

Illustrations by Toh Bee Suan

This article was originally published on 19 July 2020 as "Mala: When Ma meets La" in Science Centre Singapore's previous blog, I Saw the Science. The article has been lightly edited and includes a new conclusion paragraph for republication in Void Deck.

Last updated: 1 November 2024